The legacy of volunteers like Glen Michelson continues in a new crop of conservationists like Derek Hallgrimson. DUC hired Hallgrimson earlier this year as a conservation specialist in Strathmore, Alta.

While at Lethbridge College pursuing his bachelor of applied science in ecosystem management, Hallgrimson volunteered and served as president of the DUC Lethbridge College student chapter. This is where he first learned about Michelson.

“He’s left a big impression on the community in southern Alberta,” says Hallgrimson. He understands Michelson’s Kee-man commitment because he shares it. “It’s about appreciating an opportunity to give back.”

But as a millennial, Hallgrimson has a conservation advantage that Michelson didn’t: affordable high-tech.

“Eighty years ago, our mission was to safeguard habitat for waterfowl and wildlife. Today, that mission remains the same,” says David Howerter, DUC’s director of national conservation operations. “But now we have some pretty cool tools at our disposal.”

These new tools allow DUC researchers and conservation specialists to ask new questions, conserve more effectively, and see (and understand) the landscape in a whole new way.

“Eighty years ago, our mission was to safe-guard habitat for waterfowl and wildlife. Today, that mission remains the same. But now we have some pretty cool tools at our disposal.”

Sniff it

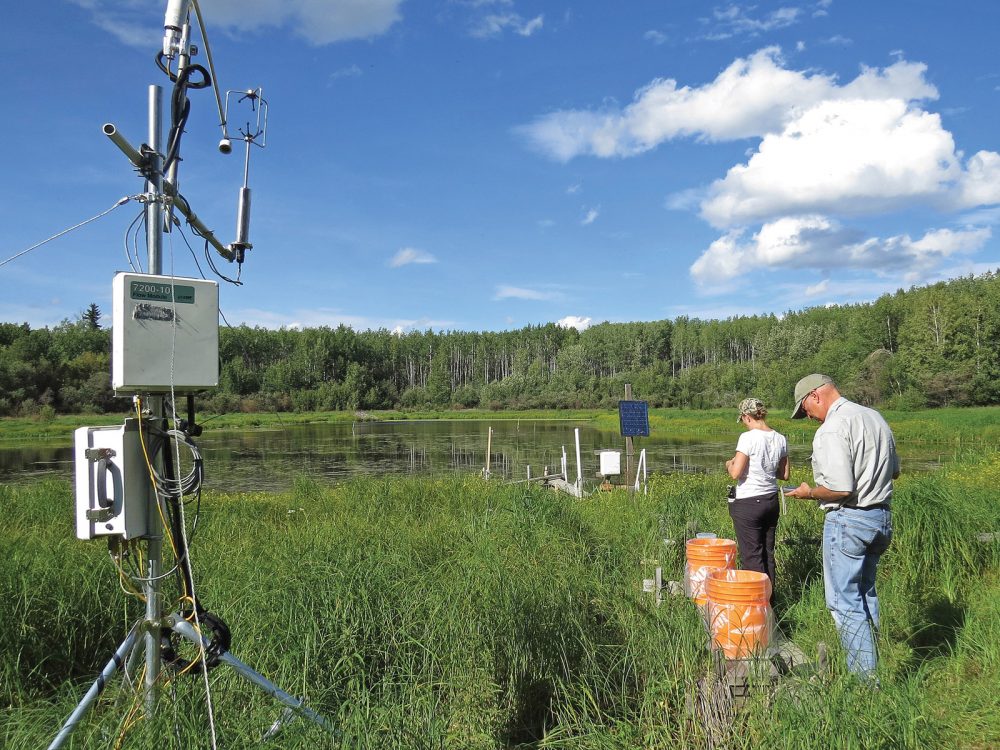

Picture a Labrador retriever with its snout to the air, picking up a scent. Its nose twitches as it identifies different smells. Now, imagine a tower with similar capabilities, looming several metres over a wetland. Instead of a superior sniffer, this machine has impressive sensors that measure methane and carbon dioxide levels, wind speed and temperature.

This is an eddy covariance system (above), and DUC researchers use the data it collects to determine fluxes of greenhouse gases at wetlands.

Tech in action

By understanding how much carbon dioxide wetlands store, DUC is equipped to advocate for their protection. Thanks to DUC’s team at the Institute for Wetland and Waterfowl Research (and technology), today we know how critical wetlands are to people, as well as wildlife.

“Conserving existing and intact wetlands is important. They’re at a point where they are acting as carbon sinks and having a net cooling effect on the atmosphere,” says Pascal Badiou, a DUC research scientist who specializes in wetland ecology.

Map it

If you’re a fan of police dramas, you’re familiar with the scene where the detective, eager to find a link between crimes, maps the location of each incident to make connections. At DUC, we use a similar approach except our goal is to understand the landscape better and help others do the same. DUC Geographic Information Systems (GIS) specialists assist with this by taking satellite-collected imagery of the earth and layering it with geographically-linked data.

Tech in action

Data-rich maps produced by GIS specialists touch almost every part of DUC’s work. In Hallgrimson’s case, he uses GIS maps to identify wetland basins on a potential landowner partner site. GIS technology is also used to predict waterfowl breeding habitat and track invasive species.

Sense it

This spring, DUC launches a pilot project that will decrease its carbon footprint by deploying Cypress Solutions Sensors (CSS) (above) at up to 25 wetlands.

“This tool will reduce staff travel while allowing us to keep constant watch over wetland projects,” says Andrew Pratt, DUC’s manager of information technology.

One hockey-puck-shaped sensor will be positioned over a wetland to monitor water levels using sonar technology. A second, smaller sensor may also be placed in the water to collect temperature readings. Powered by solar energy, both sensors will be connected to a mini computer, and data will be transmitted to DUC conservation staff via a cellular network.

Tech in action

Using CSS at places like Delta Marsh in Manitoba is important to DUC researchers trying to prevent invasive common carp from entering this world-famous wetland. The destructive carp migrate from Lake Manitoba into the wetland when water temperatures reach 10°C.

“By monitoring water temperatures remotely, we can time our installation of exclusion screens into channels that connect Delta Marsh to the lake,” says DUC research scientist Dale Wrubleski, who leads the work at Delta. “If we do this right before common carp migration, we can cut off their access to the marsh. It saves us time travelling to and from the site to determine water temperatures.”

See it

We won’t drone on about this piece of tech, but Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAV) are allowing DUC conservation staff in Saskatchewan to “see the landscape in higher resolution,” says Lyle Boychuk, a DUC GIS specialist. “The level of detail acquired now with the UAV is mind boggling,” he says.

Once a tool reserved almost exclusively for military use, drones are becoming more common in our skies. These aircrafts are piloted remotely or programmed to fly autonomously.

At DUC, trained staff program UAVs to follow a flight path, and are onsite with a controller to manage the drone at all times. The DUC Saskatchewan team use two drones outfitted with high resolution cameras, Global Positioning Systems (known as GPS) and other tech that collect detailed images and video and produce surface models of the landscape.

Tech in action

UAVs are being used to inspect and monitor DUC projects, map wetlands and document the impacts of illegal wetland drainage works. “And we’re just starting to scratch the surface,” says Boychuk, noting more uses for UAVs will likely be revealed in the near future. This bird’s eye view of the land is not just providing new information, it’s creating efficiencies. In the past, it would take up to a day or more to inspect a project that encompassed 160 acres (64.7 hectares). “Now we can image the entire property within an hour,” says Boychuk. DUC staff use drones to improve the landscape for waterfowl—not clog their skies or cause a feather-bender. “We avoid a collision at all costs,” says Boychuk.

Tried and true conservation tools

Do you remember PalmPilots? How about Betamax? Some innovations don’t stand the test of time. Others do. Here are a few basic tools that waterfowl biologists have used for decades, and will likely use for years to come.

Binoculars or field glasses

Sometimes getting up close to ducks or other wildlife is a challenge. Researchers, waterfowlers and birders alike use binoculars to watch ducks and other birds without disturbing them.

Field candler

Inspired by the poultry industry, intrepid waterfowl biologists discovered that if you place one end of a radiator hose to an unhatched duck egg and the other to your eye and hold the egg to the sun, you can see embryo development. They then know approximately when an egg will hatch.

Identification guide

Everyone needs a little help sometimes, and a good bird ID guide is a useful resource to keep on hand and reference after you’ve spotted a duck with your binoculars.

Subscribe to Conservator Magazine

The pages of Conservator magazine are filled with beautiful photography and incredible stories like this. Learn how you can receive an annual subscription when you donate to support DUC’s conservation work.

Learn more