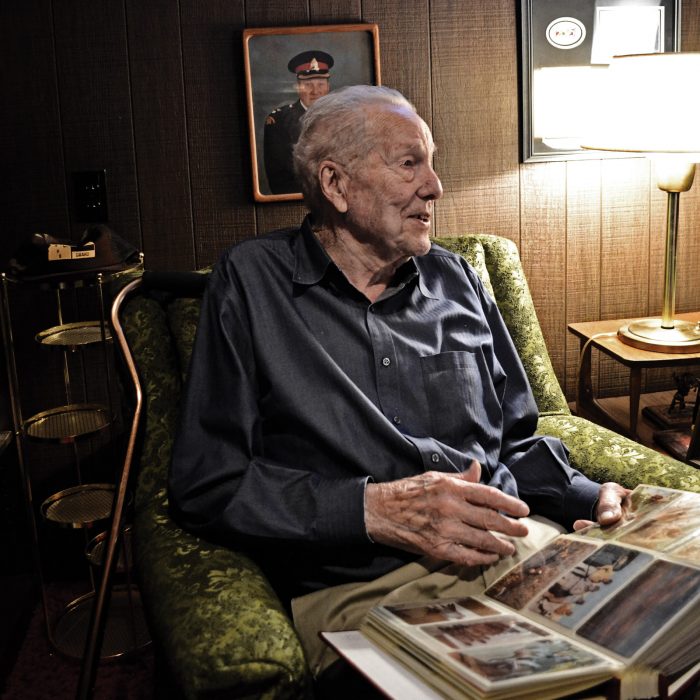

“Want me to move again?” Glen Michelson is teasing the camera operator. There are several people crowded into his Lethbridge, Alta. basement: the camera guy, a producer, and Michelson’s good friend, Ron Montgomery.

It’s the fourth time Michelson has been asked to shift his armchair to get the right camera angle. But the 94-year-old takes it in stride. The film crew wants to know about his years as a DUC volunteer Keeman. Glen Michelson is in his element.

Keemen, and Keewomen, were the eyes and ears of DUC from 1938 to 1998. They reported habitat conditions, waterfowl numbers and scouted for potential DUC wetland projects. Conservation, co-operation and restoration were their keywords. They were DUC’s original conservation volunteers and some of Canada’s first “citizen scientists.”

In late 2017, DUC issued a call for stories from and about these volunteers as part of its 80th anniversary celebrations. Montgomery responded with a lead on Michelson, who he believed was an original Keeman. How original?

Glen and his older brother Ralph began as DUC Keemen in 1939.

The brothers were born near the village of Stirling on the Michelson family farm, now a provincial historic site. They grew up trapping muskrat and mink, and hunting ducks and upland birds around nearby Stirling Lake, renowned as a wildlife and waterfowl area. Glen Michelson remembers the day in 1939 when Fred Sharp showed up to talk to them.

Sharp was DUC’s first naturalist. An old black and white photo in DUC’s archives shows a keen-eyed, slick-haired man in an iconic curling sweater with binoculars at the ready. Sharp was recruiting the Michelson brothers to the newly hatched DUC volunteer corps of Keemen. The brothers were ideally suited given their close ties to the land.

For a drought-prone area like southern Alberta, early DUC projects built to impound spring water runoff was of interest to local landowners. “Farmers welcomed DUC with open arms because it meant water for them,” says Michelson. “We really spread the word.”

Local ranchers also soon relied on these new water sources for their cattle. “These DUC projects really saved their bacon back then,” says Michelson.

Michelson enlisted with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) in the late 1940s. One of his first postings as a young officer was in Cambridge Bay, on Victoria Island, Nunavut. Even from Canada’s high Arctic, he continued to send in his Keeman reports about species like king eider. It was a duck he could get so close to when it was nesting that, he says, “you could almost touch it.”

After a brief stint with the RCMP, Michelson quit to marry his sweetheart Betty Jo. He became an inspector and fingerprint expert with the Lethbridge Police in 1950. He joined Ralph, who later became police chief.

Tall, friendly and no-nonsense, the Michelson brothers were a dynamic duo on the force, and as Keemen.

Ron Montgomery was DUC’s area manager in Lethbridge from 1983 to 1998. He got to know both Glen and Ralph during that time.

“The Michelsons knew southern Alberta so well that you could ask them about any habitat site and they would know the history and the landowners,” says Montgomery. “So they were pretty important to us on the ground.”

So dedicated were the brothers that when botulism outbreaks killed thousands of ducks in summer months, they would take a hay rack on a trailer pulled by a team of horses and fill it with dead ducks removed from the lake. Both Michelsons were also “part and parcel” of local DUC fundraisers, notes Montgomery.

“They’d attend, donate and talk to people about the banquets. To have Glen and others out there to help you get the message out was of great benefit.”

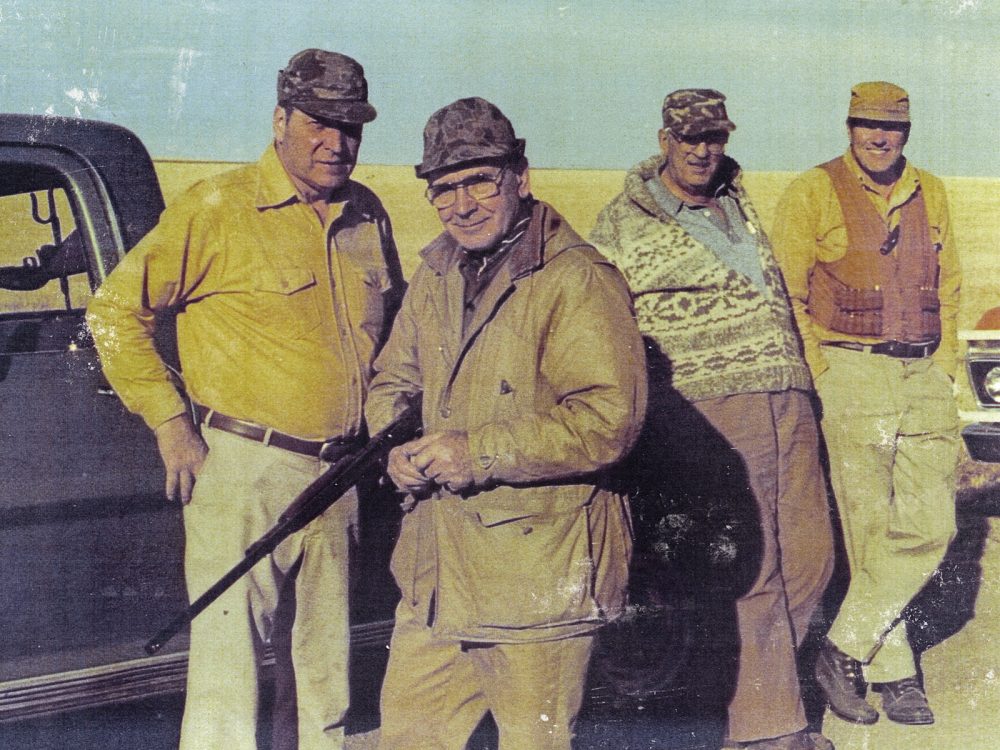

The siblings were international ambassadors for the hunting community, too. Michelson fondly recalls the many waterfowl and upland bird hunts he and Ralph hosted for a who’s who of Ducks Unlimited directors, presidents and donors, even a few FBI agents “from across the line,” who relied on the Michelsons’ well-honed instincts. They knew where the ducks were, after all.

“I’ve had lots of good years, met a lot of good guys,” says Michelson. “I keep saying that’s the good old days.”

The wife of one of the American hunters who benefitted from a Michelson-led hunt wrote to Glen to thank him after her husband died. “He’d told her it was the best hunt he’d ever had,” says Michelson.

It takes a while to set up for a camera interview. Michelson’s happy to sift through photos and chat while waiting. Once the interview gets underway, he answers questions, then veers into storytelling mode. When he does, his blue eyes light up. He’s thinking about good times and the people he enjoyed them with. Good friends like former DUC area manager “Mr. DU” George Freeman, who passed away last fall. His late brother. The many pranks he’s pulled (and still does).

And he’s thinking of a special spot, 30 minutes southeast, that’s buried under windswept snow. Soon though, the birds will be back at this place—Stirling Lake—where our original Keeman story truly began.

Nestled in surrounding grasslands, Stirling Lake had been extensively drained for agriculture use in the 1950s. DUC and government partners stabilized the lake in 1969. A decade or so later, the same partners developed an integrated management plan to ensure a fresh supply of water and other enhancements for a multi-use project.

When competing land uses threatened Stirling Lake in the 1980s, “Glen was in there fighting tooth and nail for us,” says Montgomery.

Today, the lake and surrounding uplands provides 1,442 acres (584 hectares) of valuable waterfowl production, staging and moulting habitat. It’s home to upland birds like Hungarian partridge, pheasant and sharp-tailed grouse as well as deer and other wildlife. Visitors can view the marsh from a platform and read signage about the many waterfowl species found on the project.

DUC dedicated the Stirling Lake project to Glen and Ralph in 1998, renaming it Michelsons Marsh. There’s a stone cairn and bronze plaque to commemorate their contributions.

“I have a soft spot in my heart for Ducks Unlimited. I think Ducks Unlimited is a good outfit. I think it’s good for the people, good for the country and great for the birds,” says Michelson.

“Want me to move?” jokes Michelson, one last time.

The day ends with Michelson receiving a copy of The Marsh Keepers Journey, a book published to commemorate DUC’s 75th anniversary. The gift includes a personal message from DUC CEO Karla Guyn.

Delighted, he flips through the pages, then stops at a photo showing hundreds of mallards, rising from a prairie marsh.

Ever the inquisitive citizen scientist, Michelson has a question: “Why is it that birds don’t run into each other when they are in huge flocks like that?”

He’s told that DUC scientists will get back to him with an answer.

It’s the least DUC can do for one of its original Marsh Keepers.

We happen to have a soft spot for him, too.

Kee-people: DUC’s first citizen scientists

From 1938 until the late 1990s, these citizen scientists contributed to a growing body of knowledge about the ebbs and flows of weather, water and waterfowl. Their efforts led one DUC staffer to write this message to them in 1939: “When all of your reports are brought together, we have a better picture of waterfowl conditions in Western Canada than anyone has ever had before.”

Their efforts are the basis for the habitat reports we continue to share today.

More quest finds

The Canadian Prairies proved to be a treasure trove of former Kee-people like Glen Michelson. Several contacted DUC when they read in their local papers that we were looking for stories as part of our 80th anniversary celebrations. We’d like to introduce you to a couple of them:

Don Lee – Hamiota, Man.

Keeman start date: 1982

Don Lee started as a DUC volunteer when he signed up as a Keeman in 1982. Every spring and fall, Lee made his rounds. He monitored a landscape dotted with the kinds of pothole wetlands and sloughs ducks rely on for breeding and nesting. His reports were invaluable to help guide DUC’s wetland restoration and conservation efforts in the area.

“Being raised here, you know where the water starts and ends,” says Lee. “We gave them (DUC) the eyes and ears out there and saved them from driving all over the place.”

Since then, he’s contributed countless hours as a DUC volunteer and a conservation leader in his community. He continues to share his love of the outdoors with his family.

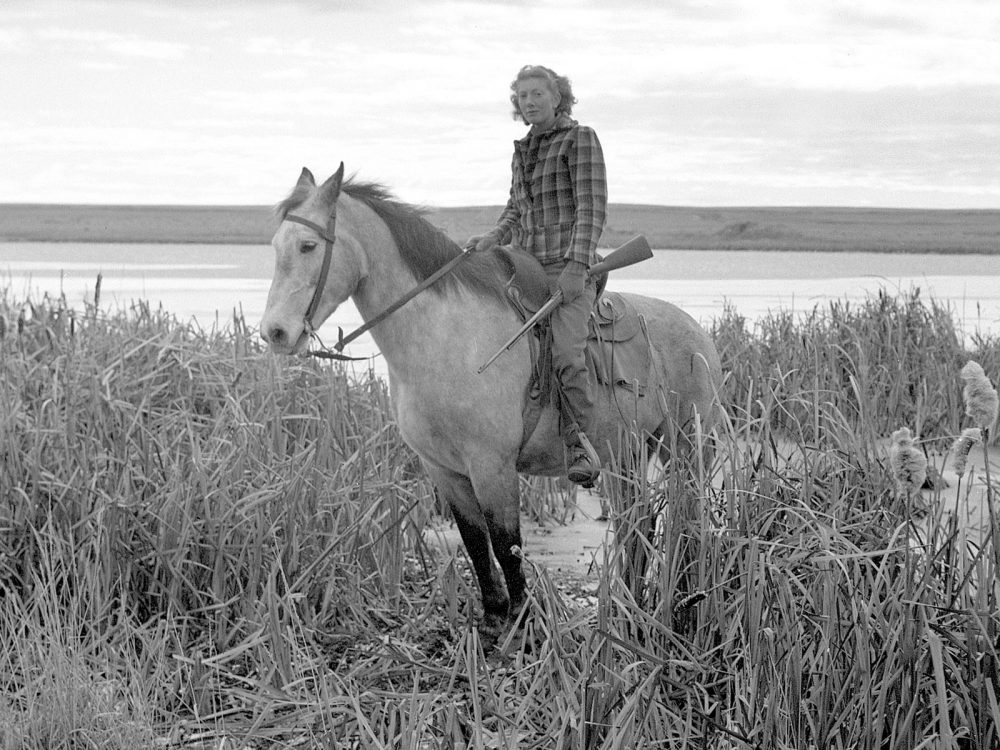

Christine Pike – Waseca, Sask.

Keewoman start date: circa 1974

She’d saddle up her horse and camp out under the stars. At dusk, she’d count ducks. At dawn, she’d start counting them again. Christine Pike (left) was one of DUC’s few Keewomen. The role combined her greatest passions: horses, ducks and protecting natural habitat around her home. Spurred on by her fierce love of the land, Pike served as a DUC volunteer from the 1970s to the 1990s.

“A great nephew—a cattleman—said to me: ‘doing anything with cattle is never work,’ so I guess counting ducks for me wasn’t work.”

Learn more about DUC’s Keeman volunteers in the Ducks Unlimited Canada podcast.

Subscribe to Conservator Magazine

The pages of Conservator magazine are filled with beautiful photography and incredible stories like this. Learn how you can receive an annual subscription when you donate to support DUC’s conservation work.

Learn more