Where the water flows

A community in the northwest territories looks to its ancestral teachings to guide the conservation path forward

Way back in history, gigantic mammals roamed the earth and fed on humans—until the day Yámoríyá arrived from the west. This is the beginning of a story, passed down from generation to generation in Dene communities across the Northwest Territories.

Yámoríyá (pronounced ya-more-ee-uh) hunted the deadly animals, including a family of large beavers that lived on the north shore of Great Bear Lake. He destroyed their lodges and killed the predators. The man-eaters were gone, and Yámoríyá had freed the people. Life went from darkness to light.

Today, the giants that terrorized the Dene people have been replaced by the symptoms of climate change: shorter ice seasons, changing weather patterns for travel, the disappearance of species, and the arrival of new ones.

But now, the people living in the remote community of Délı̨nę, NWT, aren’t looking for a Yámoríyá-like saviour. Instead, they listen to the teachings of their elders and prophets for a way forward.

Each morning Michael Neyelle, Tsa’ Tue’ (pronounced tsah-too-ay) Stewardship Council Chair and Délı̨nę resident, wakes up on the shore of Great Bear Lake, the eighth largest freshwater body in the world. Its waters are clean, cold, and pristine. “It’s the first thing that I see when I look out my window,” says Neyelle.

Locals like to collect pails of water from the lake. “Tap water’s fine, but water from the lake tastes so much better,” says Neyelle. Aside from helping produce some of the best coffee and providing locals with food, the lake and its surrounding mossy wetlands and boreal forest supports many Arctic species, including barren ground and boreal woodland caribou, wolves, wolverines, muskoxen, grizzly bears, and several species of migratory birds, like the peregrine falcon.

From Neyelle’s warm, comfortable home, the lake often appears calm, glass-like. However, he knows from experience how quickly conditions can change. “This lake is so unpredictable. It’s very dangerous,” he says. He speaks of whitecaps and rolling waves.

In one of his earliest memories of Great Bear Lake, he was a boy in a boat with his father. The lake, so large it can produce its own weather system, was still. The pair was able to travel to a bay where stretches of soft sand, as far as his young eyes could see, had replaced rocky, pebbled shores. “It was beautiful,” recalls Neyelle.

Neyelle is a wealth of information. He knows the lake, his native language, and his community. But it’s all knowledge he’s had to regain. As a young boy, he was forced to leave home to attend residential school. When he returned to Délı̨nę many years later, he’d lost his ability to live on the land and fluently speak his mother tongue. He re-immersed himself into his cultural traditions. “It was really hard, but eventually, it all came back,” says Neyelle.

Today, he sits as chair on the council and works as an interpreter. It’s a task that presents its own challenges, he says. The Sahtúgot’ı̨nę language, thousands of years old, doesn’t include terms for new words like computer, iPhone – or climate change.

Great Bear Lake and its surrounding wetlands offer immense ecological and culture values. Over the last 30 years, the Indigenous people of Délı̨nę have worked through various land claims with federal and territorial governments that allow them to control how the land is used.

“As Aboriginal people we always want to look after the land, the water, the environment and wildlife,” says former Délı̨nę Chief Leonard Kenny. “This falls under our responsibilities as Aboriginal people.”

Kenny and other members have worked tirelessly to ensure the future of the lake is secure, so it’s pristine “for all generations,” says Kenny.

This sense of responsibility was heightened by the late Dene prophet, Louie Ayah. One of Ayah’s foretellings in particular haunts Neyelle.

Ayah died in 1940. In his lifetime, he made more than 30 prophecies. One predicted the arrival of three strange animals – and in 2008, three polar bears wandered into Délı̨nę. It was a first. Marine animals generally stay close to the ocean, but these bears travelled over a thousand kilometres inland to reach the community. Another prophecy, and the one that troubles Neyelle, envisions a time when Great Bear Lake will be the final source of fresh water.

“My elders and ancestors have predicted that this will be the last lake to provide in this world, when the world gets into all these problems with food, water and, everything. Just that prediction alone makes me want to try hard to do whatever I can,” says Neyelle. “It’s something that is on my mind all the time.”

Outside the late Ayah’s home on the shore of Great Bear Lake, on a mid-August day in Délı̨nę, the sky is overcast and people wear rain coats. While rain isn’t new to the Northwest Territories, it’s becoming more common. And according to research published by the territory’s Department of Environment and Natural Resources, it’s likely to remain, as the North continues to warm.

Inside the Délı̨nę community centre, Neyelle listens intently to dignitaries from various organizations deliver speeches. He translates their words to Sahtúgot’ı̨nę, the language of his ancestors. People from across Canada, and beyond, have travelled by plane to the remote community to celebrate.

On March 19, 2016, in Lima, Peru – more than 9,400 kilometres away – Délı̨nę was recognized for its commitment to safeguarding the land and water, with a United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) International Biosphere Reserve Designation.

Described as an award of excellence, the designation recognizes a geographical area (23,058,144 acres, or 9,331,300 hectares) of land and water, where there is a balance between humans and nature. The biosphere reserve, Tsá Tué, is named for the giant beavers (tsá) Yámoríyá once chased.

Danika Littlechild, vice president of the Canadian Commission for UNESCO, is at the August celebration in Délı̨nę. As the first Indigenous woman to hold her post within the UN, Littlechild applauds the conservation work by the community of Délı̨nę. “What you have done here will have ripple effects far beyond what you can see,” she says.

How did a community of approximately 600 people garner the attention of the United Nations? According to Neyelle, there were two key ingredients: a reverence for the teachings of elders, and co-operation.

“We’ve grown up to respect our elders and when they speak, we listen,” says Neyelle.

And when it comes to co-operation, the community of Délı̨nę doesn’t just work together; they work with others outside the community, like the International Boreal Conservation Campaign (IBCC). IBCC is an initiative that teams together resources and staff from The Pew Charitable Trusts, Ducks Unlimited and other partners to conserve the boreal forest – an important breeding area for North American waterfowl.

The partner members of IBCC supported Délı̨nę’s bid for the UNESCO designation. According to Les Bogdan, Ducks Unlimited Canada’s (DUC) director of regional operations, British Columbia/boreal region – who sits as a member on the IBCC board – the partnership between residents in Délı̨nę and DUC signals a more inclusive style of conservation work.

“People tend to envision conservation taking place through science and technical reports, or in the field doing restoration work,” says Bogden. “But often it’s about forming partnerships. To conserve important lands in the boreal forest, we must work with Indigenous groups, just as we have in the community of Délı̨nę,” he says, adding that DUC provided the community with an online mapping application to support them in their land-use management.

Accessible by plane and boat, and ice roads in winter, Délı̨nę is providing a model for Indigenous-led land management. The Dene people hope their land and lake comes up in conversations of those living elsewhere in Canada and around the world.

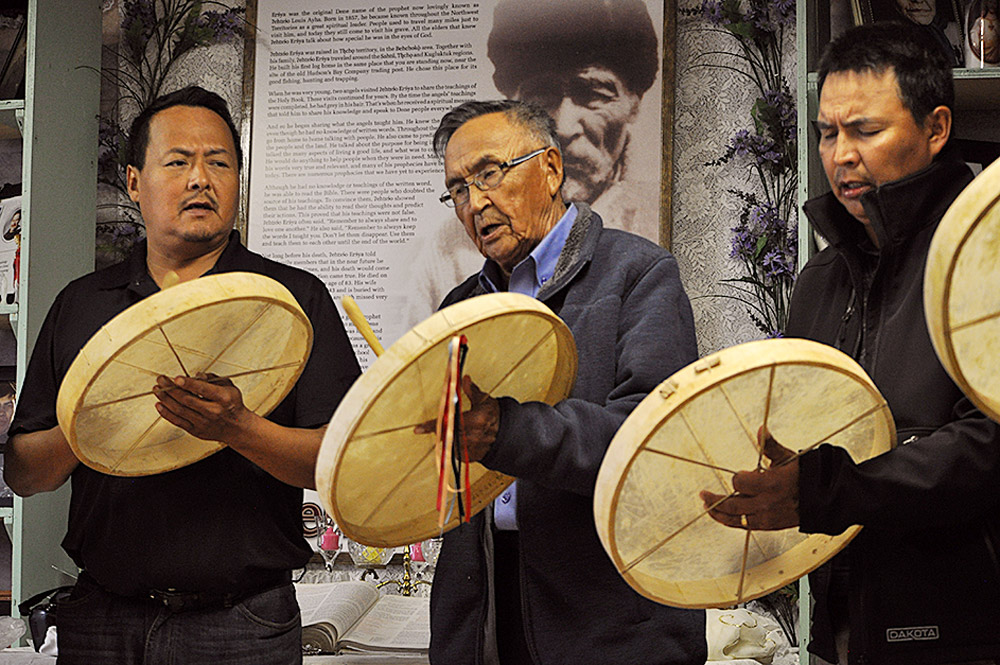

On this summer evening, young and old Dene men beat Æexele (pronounced ex-ell-eh), and people join together to dance and celebrate as one. The Dene have accepted a Yámoríyá-like task to safeguard the natural environment…for everyone.

“What we’re doing is for all Canadians, and for all youth of the world,” says Neyelle.

Délinę, delineated

- Délinę (pronounced dell-in-ay) is located in the Sahtú region of the Northwest Territories, on the western shore of Great Bear Lake. In Sahtúgot’ınęk’ gokede, the language spoken by residents, Délinę means “where the waters flow.”

- Until 1993, Délinę was called Fort Franklin, named for English explorer Sir John Franklin, who wintered in the area with his crew during their second Arctic expedition (1825-1827). Eighteen years after leaving Délinę, Franklin set out on his ill-fated mission to discover the Northwest Passage.

- On September 1, 2016, Délinę became the first community in the Northwest Territories to achieve self-governance. Délinę Got’ine Government will be funded by federal and territorial governments, and will have responsibility for services such as health care, education and housing.