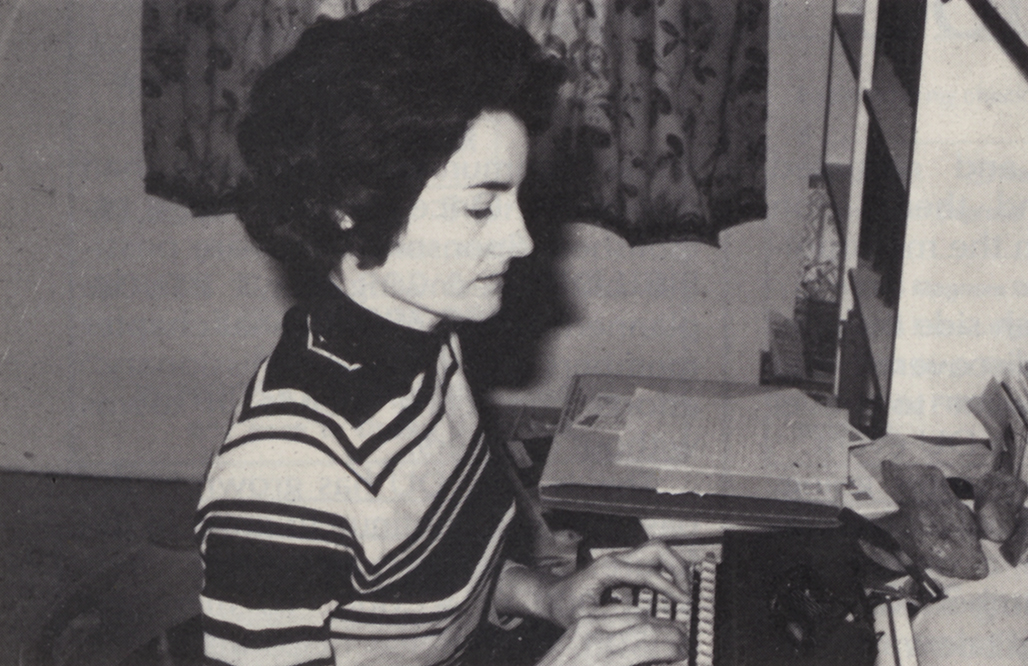

Christine Pike: Keen-Woman

Fierce love of the land spurs on 25-year Saskatchewan volunteer.

Christine Pike would pick a day in May, saddle a horse after supper, and leaving the family homestead, head to a spot she’d chosen by Big Gully Creek on Big Gully Marsh. She’d unroll a blanket and prepare to camp under the stars. At dusk, before settling in for the night, she’d count ducks. Rising at dawn, she’d start counting them again. It was a ritual she repeated every year, for several decades, starting in the 1970s.

Pike was one of DUC’s few Keewoman volunteers. She’s also a cattlewoman and horse trainer. She’s been trained as a commercial artist and as a singer. At heart, she’s a conservationist.

“I’ve fought many fights,” says Pike. This includes the 13-year battle she led (and won) to protect the mouth of Big Gully Creek from development that got even politician Tommy Douglas involved. But that’s another of Pike’s many fascinating stories.

Protecting the landscape she loves

Pike was born, raised and continues to live in the Waseca District of Saskatchewan, close to the Alberta border. It’s a landscape Pike clearly loves, and she describes the area around the mouth of Big Gully Creek as “a beautiful land with natural features like fens.”

She remembers the day in the early 1970s when Ken Smith, a conservation officer for the Battlefords, visited her with a DUC representative to recruit her as a volunteer for the Keeman Program. Keemen were DUC’s team of 300 field reporters who could deliver information about habitat conditions and waterfowl numbers in key duck-producing areas of the Prairies.

“I guess I was a good candidate since I was close to Big Gully Creek and the big marsh that was good habitat for waterfowl and a well-known duck nesting area,” says Pike. “I was old enough to see the ups and downs of waterfowl in the province,” she adds, recalling the 1950s when “the sky was black with ducks.”

Pike decided that as a Keewoman her responsibility would be Big Gully Marsh along Big Gully Creek and an area bordered by the North Saskatchewan and Battle Rivers. She was to send two reports to DUC every year, in spring and fall, detailing the waterfowl and wildlife she saw, as well as water levels and general land conditions.

For more than 20 years, until the late 1990s when the Keeman Program ended, Pike dutifully completed and sent in her reports. “They were written, fill in the blanks, checklist sorts of reports,” says Pike. “I think mine were quite boring,” she adds, laughing.

Her memories of that time are anything but.

Life as a DUC Keewoman

During one of her spring surveys, Pike says, “a trick was pulled on me by a clever Appaloosa cattle horse named Feather.” She had left the horse to graze, and at some point, the horse disappeared. “When I called her, she didn’t come. I wasn’t too worried. I sat there on an old buffalo rubbing stone. The landowner had left one gate open. I forgot, but Feather didn’t. So, she went home. Feather: the horse who loved me and left me,” Pike laughs, again, knowing that in those days her niece Ellen would come on another horse, leading Feather, in the morning.

Her fall checks of the area were easy to do, she says, “because you would see waterfowl all over the place and how good the season’s hatch was; it was always good until more recent years.”

She also has fond memories of DUC’s 50th anniversary celebrations in Winnipeg, in 1988. She was part of a contingent of DUC volunteers who descended on the city’s downtown. “There was a huge crowd there, and when we walked to the convention centre, they had to block traffic for us,” remembers Pike. “I met some wonderful people—whose names I’ve forgotten but can see their faces—who were sincere conservationists. That was their life.”

Reflecting on her time as a Keewoman, the matter-of-fact Pike is modest about her contributions. “I never thought about it—I thought, ‘this is a good job,’ so I just did it.

“A great nephew—a cattleman—said to me: ‘Doing anything with cattle is never work,’ so I guess counting ducks for me wasn’t work.”

Volunteering for a cause

After seeing the effects of the long Prairie drought of the 1990s and early 2000s, which she describes as “absolute hell around here and worse in Alberta,” Pike believes actions to keep natural features like wetlands on the landscape are critical. “DUC’s small dams are often of great value; they hold water back and still let a little water go. It’s good for wildlife and waterfowl.”

Pike continues to monitor the land and the skies. The autumn of 2016 was a spectacular year for swans, she says. “We had thousands of migrating swans all over—it was a delight—and thousands of geese passing over Maidstone,” she recalls. And in spring 2017, she adds, there were two sets of duck hatches.

“I still watch. I love birds.”